| John Broskie's Guide to Tube Circuit Analysis & Design |

30 July 2007  I'm Back I'm Back It was in turn hot, rainy, overcast, and sunny—but always wet. The American East Coast is beautifully green, but unbearably humid. The sharp distinction between land and sea blurs in New Jersey, where insects fly/swim (flim?) in a stew-thick steam bath of moisture. Golden California, in contrast, is hot, sunny, and completely dry in the summer. (Well, at least such is the area where I live, i.e. the Central Valley.) By the way, the Golden State got its nickname not from the gold found there a hundred years ago, but for the burnt gold color of the grassy mountains in the hot summer drought.

If I sound a bit grumpy, perhaps it is because not only does this nearly-lifelong Californian despise humidity to the depths of his being, but I drove over 1,000 miles on the East Coast, home of some of the worst traffic I have ever known. Hours of crawling at 10 mph gave me plenty of time to come up with a solution, however: do away with government-induced traffic jams. Unlike most of the country, the northeastern U.S. stubbornly clings to an old-fashioned government shakedown of its citizens known as toll roads. If you don’t know what a toll road is, you are very lucky indeed. Imagine getting on a public road that made you slowly crawl for a mile or two and then stop completely and then slowly inch your way up to a pay booth where you must pay for the privilege of having suffered a state-sponsored traffic jam; and imagine seeing where you wish to turn off, but not being able to turn off--as once you are on a toll road, you are stuck on a toll road, as there is no exit until the next toll-collecting center, which can be many towns away. I have had less hassle getting out of health-club contracts than breaking free of one Pennsylvania toll-road. I had made a wrong turn and I had to drive ten miles (and pay twice) before being able to turn around. If my car had broken down on me, I would have had to hike for miles to escape, although I was in a dense urban setting, not the middle of the Utah Salt Flats. Oh yes, the painful irony of being able to see where I needed to go as I made my wrong turn, but being forced to run down a long tunnel of road for twenty miles before I could start again. I am not alone in hating toll roads. Citizens in New Jersey have started www.EndTolls.com, the website of Citizens Against Tolls. In England, the National Alliance Against Tolls runs the www.notolls.org.uk/ website. But most believe that like taxes and death and diamonds, toll roads are forever. Here’s the problem: say that New Jersey bans toll roads and unshackles its public roads, not only will the state lose revenue, but none of the adjoining states is likely to follow...which means that the state of New Jersey will feel the most acute form of envy and anger at the out-of-state driver who will drive free in New Jersey, while New Jersey drivers get soaked by the other states. Besides, getting any government to ease up on taxing is as effortless as convincing a heroin addict to ease up on free smack. In other words, I just cannot see any one state breaking free of the nasty habit. So, what’s the solution? Just as President Gerald Ford signed into law the Federal-Aid Highway Amendments of 1974, which forced an insanely low 55 mph nationwide speed limit, President Bush should push for a “Public Roads Are Free Roads” amendment, with the only exceptions being privately owned toll roads. Unlike peace in the Middle East, free public roads are something that is possible. The more I think about it, could not the amendment be titled the “Free Public Road Global Warming Reduction Amendment”? Obviously, having a million cars a day crawl at 5 mph and then stop with the engines running can only needlessly increase the cars' carbon contribution. Add to that the stupid limiting of toll road on-ramps and exits which causes many drivers to drive too far in both directions and then to double back on side streets to get where they are going, which undoubtedly wastes fuel and pollutes more. Let's get the global warming lobby into this, and we can kill the toll road in our own time.

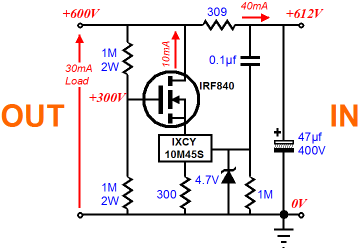

Higher-Voltage Feedforward-Shunt Regulator

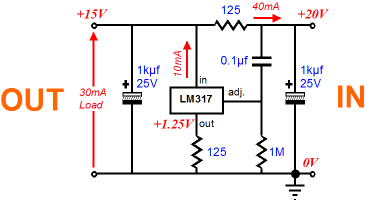

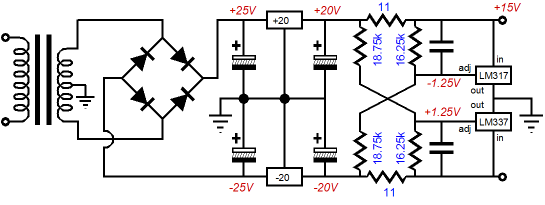

Low-Voltage Feedforward-Shunt Regulator

Although the LM317 is transistor-based, it effectively functions as a depletion-mode device, as it can conduct current with its adjustment pin being negative to its output. To set the idle current through the device, just divide 1.24V by the desired idle current. For example, in the schematic above, the 125-ohm resistor at the LM317’s output and ground force a conduction of 10mA through the regulator. The downside to this low-voltage feedforward shunt regulator is the poor output impedance, in spite of its quite stellar PSRR figure. Adding a series voltage regulator can dramatically reduce the output impedance and provide a fixed output voltage.

Creating a negative version is easy enough with the LM337. In fact, a bipolar power supply might allow the easy use of shunt post regulators instead of series regulators, with the LM317 and LM337 along the lines of what was described in blog number 109:

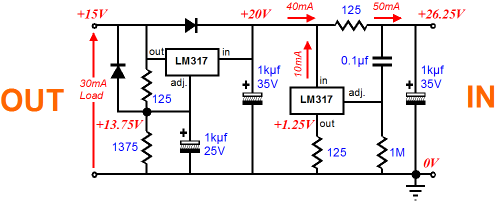

But as the feedforward shunt regulators do no provide a fixed output voltage, we will have supply two voltage references. Imagine replacing the two 16.26k feedback resistors in the schematic above with 16.25V zeners, as one possible configuration.

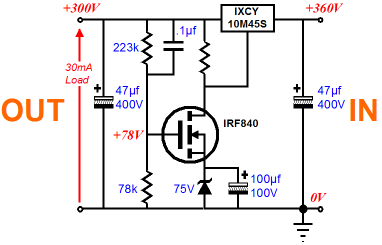

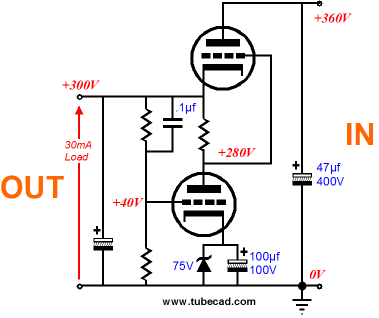

Push-Pull/Series-Shunt High-Voltage Regulator

The IXCY 10M45S could be replaced by a triode, as could the IRF840, which would make the SRPP-like topology obvious.

Now imagine that the bottom triode were replaced by a pentode and that the pentode's screen attached to the raw B+ connection. Such a configuration might work to bring a feedforward-shunt aspect to the regulator.

Next Time //JRB

|

|

| www.tubecad.com Copyright © 1999-2007 GlassWare All Rights Reserved |