| John Broskie's Guide to Tube Circuit Analysis & Design |

05 September 2006

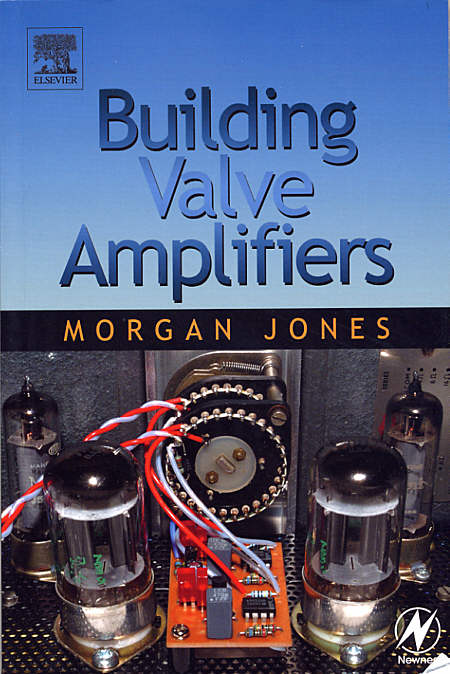

Book Review

In other words, both books complement each other and can be viewed as a two-volume set. (At over 350 pages, this book is too large to have been tacked on as an appendix to Valve Amplifiers. In addition, I can imagine his publishers doing the math: we can add half again as many pages to the first book and raise the $49.95 price by maybe 15% to 25% or we can bring the book out on its own and sell it for $33.95. Do not get me wrong, I am happy to pay for two books and I prefer many smaller books to one fat book; after decades of reading 1,000-page computer reference books, books so heavy that one dropped from a window could lead to murder charges, I long for easy-to-read-in-bed sized books.) The punch line is that I very much like this book and I lend it my unalloyed recommendation. Having said that I must admit my prejudices. First, I have met Morgan Jones and we occasionally e-mail back and forth. He is jewel of a fellow and I cannot imagine not instantly liking him. Considering how large is the ratio of charlatans, conmen, and imposters in high-end audio, he stands out as a genuine NOS Genalex KT88 in a crate otherwise filled with Chinese 6L6s. Second, I hate trying to fix other audiophiles’ broken home-built tube gear. And the only thing worse is trying to do so over the phone or through e-mail. Unlike commercially-built gear, these boat-anchors in waiting may never have worked. Given that fact, how does one sort out the crux of the problem–and long distance, at that–bad component, bad wiring, bad layout, under-specified parts…? I have seen it all: 450-volt power supply capacitors burdened with a 550-volt power supply, grid-stopper-free amplifiers that oscilate at full power at 90MHz, ground buses that look they were designed with the aid of a spiral graph (or illicit drugs), backward rectifiers, huge solder joints the size of cherry pits, heavy coupling capacitors tack soldered in place so flimsily that they easily shake lose and fall to the floor, high-voltage-carrying wire protruding from the chassis. Thus, in terms of my workload, I can only benefit from more tube-loving audiophiles reading this book. Third, he uses the Broskie-Cavalli-Jones headphone amplifier as one of his practical examples, which was a pleasant surprise. (It was Alex Cavalli who introduced me to Morgan Jones.) So now that you know that I like Building Valve Amplifiers, why should you like it too? To start, it is well written. Jones writes the way I wish all technical books were written: to the point, clearly, and with a human touch. Explaining carefully, but never excessively, Jones is out neither to impress nor to intimidate. In fact, portions of the book have the slight feel of a confessional, as if it were a catalog of how not to make the mistakes he once made. In fact, he states in the preface,

Furthermore, I don’t know where else you would find much of what is covered in Building Valve Amplifiers, particularly the material found in the half devoted to testing. I know that “testing” is a naughty word for many audiophiles, who fear getting too technical might undo some of the glory of their single-plate 2A3s. And many solder slingers are boldly lazy; they maintain that all the testing that is needed is to flick on the power switch, as the equipment will either work or not work. If only that were true. Analog gear is like life itself, where Perfect Health and Death are but thin lines that bracket a huge expanse of gray area that is filled with varying degrees of tiredness, decay, illness, atrophy, enfeeblement, and stupor. No amplifier works perfectly; each bends and twists the input signal in its own way, as none of its parts is perfect; nor is any immutable, as time ages all that is physical. Testing allows us to see into the gray. It reveals problems that no amount of tube rolling or part-brand swapping will solve. Furthermore, testing promotes understanding more effectively than any other means. If you want to know how an amplifier works, test it, with your ears, a scope, an FFT, and whatever other tools you have available. In addition, audio testing, like racecar testing, is neither as simple nor as obvious as Consumer Reports would have us believe. Did you know that tube amplifiers can suffer from slew-limmited distortion? They can, and do you know how to test for it? Building Valve Amplifiers expalins how. A key point here is that audio electronics has its own subtleties and important details that do not appear on the radar of most other electronic undertakings. For example, as long as a digital clock keeps accurate time, it little matters if its power supply suffers from poor regulation, ground loops, or high noise. Moreover, Building Valve Amplifiers is gently suffused with Briticisms and English good humor (or should I have written, “humour”?). For example, in listing the many construction faults revealed in an illustration, he writes: “Gaffer tape is for bodging on stages and studio floors, not internal electronic use.” In conclusion, I don't know of a better way to spend $30* and get so much useful information on building tube amplifiers. Morgan Jones has done us all a great favor by writing Building Valve Amplifiers. We should return the favor by buying it and defending it. Defending? Unfortunately, I expect this book may not get a fair press. Why? One reason that readily comes to mind is that for every tube-loving audiophile there are at least ten tube-loving musicians. Tube-based music amplifiers are to high-end tube amplifiers what country music is to classical music: related, but neither wishes to admit it. In other words, because of Google searches for tube amplifiers, ten times as many music-amplifier folk will come across Jones’s book, and they won’t get it, just as they won’t get his Valve Amplifiers; it’s more of a culture-based blindness, rather than a mental deficiency (of course years of drug use doesn’t help). The book’s example circuits will look strange and unsettling to them. “Constant-current source? What the hell is a constant-current source," they will wonder. On the other hand, solid-state-loving audiophiles and musicians will not even vex themselves by looking at Building Valve Amplifiers, but then at least they will not bother leaving a disagreeable review at Amazon. So far there are three reviews at Amazon; one gave only two stars becuase the book wasn't more like Jones' Valve Amplifiers and another gave it only three stars because it did not cover his music amplifier interests (only the last reviewer understood the book's value and gave it the five stars it deserved). Prove these jokers wrong, and buy and support Building Valve Amplifiers.

Next time //JRB

* I found copies of Building Valve Amplifiers selling for as little as $30 on the web, but since Amazon offers free shipping, its $33.95 price might ultimately prove the cheapest. In fact, I toyed with the idea of buying a case of Building Valve Amplifiers directly from the publisher (Newnes, an imprint of Elsevier) and having it shipped to Morgan's house, where he could sign each copy, as I would love to sell his signed books at my Yahoo store. I know that I would gladly pay $10 more for a signed copy, but that wouldn't cover the shipping costs from England, so I dropped the idea. (Aikido PCB buyers have asked me to sign thier boards! Can you believe it?)

|

Aikido PCBs for as little as $24 WHAT IS AN AIKIDO AMPLIFIER?

The Aikido tube topology, created by John Broskie, delivers the sonic goods. Since the Aikido circuit came out in the Tube CAD Journal, people have been building it and marveling at its sound. A prediction: just as the 1980s were the cascode decade and the 1990s, the SRPP decade, this decade will be known as the Aikido decade. Why? This amplifier circuit offers voltage gain, low distortion, low output impedance, and a high PSRR figure—all without a global feedback loop. Better than SRPP Flexible Always Biases Up Correctly Functions Flawlessly No Popping Sounds at Startup, Less Distortion A Sound that’s Hard to Improve Upon AIKIDO AMPLIFIER PCB What makes them superior? First of all, they look fabulous and feel solid in the hand: extra thick (inserting and pulling tubes from their sockets won’t bend or break this board), double-sided, with 2oz copper traces, clean silkscreen and solder mask. (The board holds two sets of differently spaced solder pads for each resistor, so that radial and axial resistors can be easily used. Each capacitor finds several solder pads, so wildly differing sized coupling capacitors can neatly be placed on the board.) Each board holds two Aikido linestage amplifiers; so, one board for stereo unbalanced or one board for one channel of balanced amplification. The boards hold two coupling capacitors, each finding its own 1M resistor to ground. The idea here is that you can select (via a rotary switch) between C1 or C2 or both capacitors in parallel. Why? One coupling capacitor can be Teflon and the other oil, or polypropylene or wax and paper…. As they used to sing in a candy bar commercial: “Sometimes you feel like a nut; sometimes you don't.” each type of capacitor has its virtues and failings. So, use one type of coupling capacitors for old Frank Sinatra recordings and the other for string quartets. Or the same flavor capacitor can fill both spots: one capacitor would set a low-frequency cutoff of 80Hz for background or late night listening; the other capacitor, 5Hz for full range listening. Or if you have found the perfect type of coupling capacitor, the two capacitors could be hardwired together on the PCB, one acting as a bypass capacitor for the other. The board assumes that a DC 12V power supply will be used for the heaters, so that 6.3V heater tubes (like the 6SL7 and 6SN7) or 12.6V tubes (like the 12SL7 or 12SN7) can be used, for example on an octal board. Both types can be used exclusively, or simultaneously; for example 12SX7 for the input tube and a 6BX7 for the output tube. (A 6V heater power supply can be used, as long as all the tubes used have 6.3V heaters; and an AC heater power supply can be used, if the heater shunting capacitors are left off the board.) The boards are four inches by ten inches, with eight mounting holes. Boards are made in the USA and come with instructions that include schematic and recommended part values. A real E-mail from a new Aikido PCB owner:

Visit our Yahoo Store for more details: | |||

| www.tubecad.com Copyright © 1999-2006 GlassWare All Rights Reserved |